ΚΟΙΝΩΝΙΚΟ ΘΕΑΤΡΟ: ΘΕΑΤΡΟ ΤΗΣ ΚΟΙΝΟΤΗΤΑΣ & ΘΕΑΤΡΟ ΤΟΥ ΚΑΤΑΠΙΕΣΜΕΝΟΥ

Μάρθα Κατσαρίδου[1]*

Koldo Vío[2]**

DOWNLOAD FILE:

Κοινωνικό Θέατρο_GR

0C Social Theatre_EN

Το Κοινωνικό Θέατρο

Το Κοινωνικό Θέατρο αποτελεί μία από τις βασικές περιοχές του Εφαρμοσμένου Θεάτρου που στοχεύει στην κοινωνική δράση/παρέμβαση, τη συμμετοχή, την ενδυνάμωση και τελικά τον κοινωνικό μετασχηματισμό. «Η τέχνη δεν είναι μόνο αναπόληση, αλλά και δράση, και όπως κάθε δράση δύναται να αλλάξει τον κόσμο, έστω και λίγο» (Tony Kushner στο Nicholson 2014, 10).

O όρος Κοινωνικό Θέατρο χρησιμοποιείται ευρέως από χώρες όπως η Ιταλία, η Ισπανία, η Πορτογαλία και τελευταία και η Ελλάδα, ενώ αντίστοιχα στον αγγλοσαξονικό χώρo χρησιμοποιούνται πιο συχνά οι όροι community-based theatre, popular theatre, theatre for development, theatre for social intervention. Ιδιαίτερη αναφορά, όμως, χρειάζεται να γίνει στους Richard Schechner και James Τhompson (2004), οι οποίοι προέρχονται από τον χώρο των performance studies και υιοθετούν τον όρο Κοινωνικό Θέατρο, αναζητώντας μια ενοποιητική γραμμή για τις μορφές που μπορεί να πάρει. Συγκεκριμένα ως Κοινωνικό ορίζεται το Θέατρο που έχει συγκεκριμένη κοινωνική ατζέντα∙ το θέατρο που η αισθητική δεν είναι ο κυρίαρχος στόχος∙ το θέατρο που βρίσκεται εκτός του καθεστώτος της αγοράς, που κινεί το Broadway/West End, και εκτός του καθεστώτος της λατρείας της καινοτοµίας, που κυριαρχεί στην avant guarde (Thompson & Schechner 2004, 12).

Για τους ίδιους, το Κοινωνικό Θέατρο μπορεί να λαμβάνει χώρα σε ποικίλα μέρη με διαφορετικούς/ες συμμετέχοντες/ουσες. Παραδείγματα χώρων αποτελούν οι φυλακές, οι χώροι υποδοχής προσφύγων, τα νοσοκομεία, τα σχολεία, τα ορφανοτροφεία, οι οίκοι ευγηρίας. Αντίστοιχα, οι συµµετέχοντες/ουσες σε δράσεις Κοινωνικού Θεάτρου μπορεί να είναι ντόπιοι κάτοικοι, άτομα με ειδικές ανάγκες, πρόσφυγες, φυλακισμένοι/ες και ευρύτερα άτομα που ανήκουν σε ευάλωτες, μη προνομιούχες και περιθωριοποιημένες ομάδες. Επίσης, μπορεί να είναι άτομα που έχουν χάσει την αίσθηση του «ανήκειν» σε μια ομάδα, άτομα που είναι εσωτερικά και εξωτερικά παραγκωνισμένα.

Σε γενικές γραμμές το Κοινωνικό Θέατρο επιτελείται σε μέρη και υπό συνθήκες που δεν νοούνται τυπικά ως «θέατρο». Οι εμψυχωτές/τριες του Κοινωνικού Θεάτρου είναι συνήθως επαγγελματίες –συχνά καλλιτέχνες, χωρίς αυτό να είναι απαραίτητο– και λειτουργούν περισσότερο ως «διευκολυντές», βοηθώντας την ομάδα να συµµετάσχει ενεργά συμμετέχοντας και οι ίδιοι/ιες στη διαδικασία. Οι συµµετέχοντες/ουσες, από την άλλη, είναι μη επαγγελματίες θεάτρου, «µη ηθοποιοί», οι οποίοι/ες κατά τη διάρκεια της δράσης μετατρέπονται σε ηθοποιοί (Thompson & Schechner 2004, 12, Βασιλειάδη 2012, 17).

Ακολούθως επιλέγονται και αναλύονται δύο πολύ σημαντικές μορφές Κοινωνικού Θεάτρου, μορφές που συνδέονται με την κοινωνική δράση και αλλαγή.

To Θέατρο της Kοινότητας

Το Θέατρο της Κοινότητας έχει τις ρίζες του σε ένα πολύ συγκεκριμένο πλαίσιο μέσα στο οποίο το περιεχόμενο, οι συμμετέχοντες/ουσες και τα θέματα είναι τοπικά. Η ποικιλομορφία που διακρίνει τις μορφές και τις παραστάσεις του Θεάτρου της Κοινότητας, έχει οδηγήσει και στην ανάγκη χρήσης διαφορετικών όρων, που να περιγράφουν την καθεμιά περίπτωση. Οι Prendergast και Saxton (2009, 135) αναφέρουν ενδεικτικά τους εξής όρους: “grassroots theatre”, “local theatre”, “ensemble theatre”, “people’s theatre.” Όποιος και αν είναι ο όρος που κάθε φορά χρησιμοποιείται, η έμφαση δίνεται στη δημιουργία και την επιτέλεση των ιστοριών της κοινότητας και των μελών της ως πρωτότυπες επαγγελματικές παραγωγές που είναι ειδικά τοπικές. Αυτές οι ιστορίες μπορεί να είναι εορταστικού ή κριτικού χαρακτήρα ή και ένας συνδυασμός των δύο. Οι Prendergast και Saxton διαχωρίζουν τους όρους “community based theatre” και “community theatre”, υποστηρίζοντας ότι ο πρώτος ως μορφή Εφαρμοσμένου Θεάτρου αφορά σε επαγγελματικό θέατρο ενώ ο δεύτερος αφορά σε ερασιτεχνικές θεατρικές παραστάσεις, όπου παρουσιάζονται παλιότερα σενάρια σε τυχαία ακροατήρια.

Σε μελέτη του ο John Bull σημειώνει τις διάφορες μορφές Θεάτρου της Κοινότητας, που συναντάμε, προκειμένου να αναλογιστούμε τα σημαντικά θέματα που προκύπτουν, όταν γίνεται προσπάθεια κατηγοριοποίησης του Θεάτρου Κοινότητας (Bull στο Billingham 2005, 9).

Συγκεκριμένα, διακρίνει τις εξής μορφές: α) ερασιτεχνικές θεατρικές οµάδες της κοινότητας (amateur community theatre groups), β) θεατρικές οµάδες νέων (youth theatre groups), γ) θέατρο της κοινότητας στο επαγγελµατικό θέατρο (community theatre in the professional theatre) δ) θέατρο στην εκπαίδευση (Theatre-in-Education), ε) εκπαιδευτική οµάδα της κοινότητας (educational community group), στ) επαγγελματικές θεατρικές οµάδες µε ιδιαίτερα ενδιαφέροντα (special interest theatre companies), ζ) θέατρο στον χώρο εργασίας (theatre in the workplace), η) μεμονωμένες γιορτές της κοινότητας, φεστιβάλ (one-off celebrations, festivals), θ) θέατρο μέσα από την κοινότητα (theatre from within the community), ι) θέατρο για την κοινότητα (theatre for the community) (Bull στο Billingham 2005, 9-11).

Από τα παραπάνω διαπιστώνεται ότι ο όρος «Θέατρο της Κοινότητας» χρησιμοποιείται ποικιλοτρόπως για να περιγράψει μορφές θεάτρου που διαφοροποιούνται κατά πολύ μεταξύ τους ανάλογα τον στόχο, το κίνητρο συμμετοχής, το πλαίσιο παρουσίασης της παράστασης, τον χώρο που επιλέγεται και το κοινό που απευθύνεται, τη χρηματοδότηση που λαμβάνει κ.α.

Ο Bull υποστηρίζει ότι κατά βάση αυτό το θέμα προκύπτει, καθώς, όπως συνήθως συμβαίνει με άλλους κοινωνικούς και πολιτιστικούς όρους, η έννοια της κοινότητας δεν είναι ουδέτερη. Εκκινώντας από τη λατινική ρίζα communitatem, η χρήση της έχει συνδεθεί µε τo μοίρασμα κοινών ενδιαφερόντων μεταξύ των ατόμων, καθώς επίσης, και το μοίρασμα ενός κοινού για όλους τόπο. Η έννοια της κοινότητας µπορεί να θεωρηθεί κάτι παραπάνω από µια οµάδα ανθρώπων που τυχαίνει να ζουν σε µια συγκεκριµένη περιοχή αντί για µια άλλη˙ αντιθέτως, πρόκειται για μια πιο ουσιαστική σύνδεση, που πιθανόν εκκινεί από την κοινή γεωγραφική τοποθέτηση των ατόμων, τα οποία μοιράζονται μια αίσθηση κοινής και ομαδικής ιδεολογίας (είτε πολιτική είτε ταξική) και που δύναται να καθορίζεται σύμφωνα με ζητήματα όπως η σεξουαλικότητα, το φύλο, η καταγωγή, οι θρησκευτικές πεποιθήσεις ή οτιδήποτε άλλο (Bull στο Billingham 2005, 11).

Σύμφωνα με τις παραπάνω κατηγορίες, ιδιαίτερο ενδιαφέρον παρουσιάζει το γεγονός ότι ανάλογα με τη μορφή του Θεάτρου της Κοινότητας, η συμμετοχή των μελών της κοινότητας μπορεί να διαφοροποιείται, όμως η κοινωνική δράση και παρέμβαση για την ίδια την κοινότητα παραμένει σταθερή. Για παράδειγμα στην κατηγορία «Θέατρο µέσα από την Κοινότητα» όλη η διαδικασία –από τους συντελεστές που συμμετέχουν, στο θεατρικό κείμενο που είτε γράφεται από ένα μέλος της κοινότητας είτε αποτελεί αντικείμενο συλλογικής δημιουργίας, έως τη χρηματοδότηση που δίνεται– βασίζεται αποκλειστικά στην ίδια την κοινότητα. Στόχος είναι να δοθούν στα υπόλοιπα μέλη της κοινότητας αφηγήσεις και προσωπικές ιστορίες που αφορούν όλους και όλες. Ο χώρος της θεατρικής δράσης μπορεί να είναι κάποιο τοπικό θέατρο ή ακόμη ένας οποιοσδήποτε μη θεατρικός χώρος.

Για τον Bull, στενά συνδεδεμένη με την παραπάνω μορφή είναι «το Θέατρο για την Κοινότητα» με την ειδοποιό διαφορά ότι σε αυτήν την κατηγορία εμπλέκονται επαγγελματικές θεατρικές ομάδες, οι οποίες για ένα χρονικό διάστημα δουλεύουν μέσα και για μια συγκεκριμένη κοινότητα. Σαφώς, καθώς η παράσταση που ανεβαίνει από τους/τις επαγγελματίες του χώρου αφορά σε συγκεκριμένα θέματα της κοινότητας, χρειάζεται απαραιτήτως η στενή και ειλικρινής συνεργασία του θιάσου με τα ίδια τα μέλη της κοινότητας. Τα θέματα των παραστάσεων επιλέγονται ύστερα από σχετική έρευνα των συνεργαζόμενων καλλιτεχνών με την κοινότητα και παρουσιάζονται θεατρικά από επαγγελματίες καλλιτέχνες μπροστά σε αυτή. Στόχος των παραστάσεων είναι η αφήγηση της ζωής της κοινότητας και της ιστορίας της. Έτσι, στην παράσταση, τα μέλη της κοινότητας έρχονται αντιμέτωπα με τον εαυτό τους, την οπτική γωνία που τα ίδια υιοθετούν για τα πράγματα και την οπτική που θέτει η παράσταση για τα τοπικά γεγονότα, προβληματίζονται, συνδέουν το ατομικό ενδιαφέρον με τη συλλογική συνείδηση και ανάλογα με τον βαθμό της συμμετοχής του κοινού στη θεατρική δράση, η εμπειρία μπορεί να καταστεί από ψυχαγωγική έως θεραπευτική (Bull στο Billingham 2005, 10-11, Βασιλειάδου 2012, 12-13).

Σε αυτό το σημείο και προκειμένου να αναλύσει τη συνεργασία εμψυχωτών/τριών και εξωτερικών συνεργατών με μια κοινότητα, ώστε να συζητηθούν τα θέματά της μέσα από τη θεατρική γλώσσα, ο Bull προτείνει τον όρο «παρεμβατικό θέατρο της κοινότητας», δηλαδή το θέατρο που επιδιώκει να επηρεάσει άμεσα τις ζωές των μελών της κοινότητας (interventionist community theatre) (Bull στο Billingham 2005, 13). Η έννοια της κοινότητας, που συνδέεται με τις ιδιαιτερότητες της εκάστοτε περιοχής, είναι κεντρική σε πολλά προγράμματα και πολύ συχνά λειτουργεί για να προσφέρει ένα εναλλακτικό όραμα για το πώς ήταν τα πράγματα ή πώς μπορεί να είναι στο μέλλον.

Το Θέατρο του Καταπιεσμένου: βασικές αρχές

O Augusto Boal, βραζιλιάνος σκηνοθέτης θεάτρου, παιδαγωγός θεάτρου, συγγραφέας, δραματουργός και πολιτικός είναι ο δημιουργός του Θεάτρου του Καταπιεσμένου (Theatre of the Oppressed), εφεξής ΘτΚ.

Το ΘτΚ ως θεωρητικό πλαίσιο και ως αισθητική προσέγγιση βασίζεται σε θεατρικές ασκήσεις-παιχνίδια και σε δραματικές τεχνικές, που συνθέτουν ένα διαδραστικό και συμμετοχικό είδος θεάτρου με στόχο την κοινωνική αλλαγή.

«Είμαστε όλοι ηθοποιοί: το να είσαι πολίτης δεν σημαίνει ότι ζεις σε μια κοινωνία, σημαίνει ότι την αλλάζεις» αναφέρει χαρακτηριστικά ο Boal στο μήνυμα της Παγκόσμιας Ημέρας του Θεάτρου 2009 (Boal 2009).

Θέτοντας ως στόχο την κριτική συνειδητοποίηση της πραγματικότητας και την αναζήτηση εναλλακτικών σε κοινωνικά, διαπροσωπικά και προσωπικά προβλήματα, το ΘτΚ βασίζεται στo έργο του Paulo Freire, Παιδαγωγική του Καταπιεσμένου. Το συγκεκριμένο βιβλίο αποτέλεσε σταθμό αργότερα για το κίνημα της Κριτικής Παιδαγωγικής, δηλαδή, το ρεύμα θεωρητικής παιδαγωγικής σκέψης και εκπαιδευτικής πρακτικής που εμφανίστηκε στην αρχή της δεκαετίας του 1980 στις Η.Π.Α.

Για τον Augusto Boal, το θέατρο και πιο συγκεκριμένα η «Ποιητική του Καταπιεσμένου» είναι πρώτα πρώτα ποιητική μιας απελευθέρωσης. Ο θεατής δεν μεταβιβάζει κανένα δικαίωμα για να δράσουν ή να σκεφτούν άλλοι στη θέση του. Απελευθερώνεται, δρα και σκέφτεται για τον εαυτό του. Το θέατρο είναι δράση (Mποάλ 1981, 54, Κατσαρίδου 2014, 78). Συγκεκριμένα, ο Boal αναφέρει ότι το θέατρο πρέπει είναι μια πρόβα για δράση του ατόμου στην πραγματική ζωή και όχι αυτοσκοπός (Boal 2006, 6). Ο Boal αντιμετωπίζει το θέατρο ως μια «γλώσσα», μια γλώσσα που μπορεί να χρησιμοποιηθεί από οποιονδήποτε, είτε έχει κλίση είτε όχι στον καλλιτεχνικό τομέα. Θέλει να δείξει στην πράξη πώς το θέατρο μπορεί να μπει στην υπηρεσία των καταπιεσμένων για να εκφράσουν, χρησιμοποιώντας αυτή την καινούρια γλώσσα, καινούριους τρόπους επικοινωνίας (Μποάλ 1981, 16).

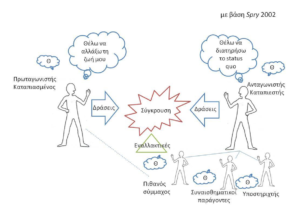

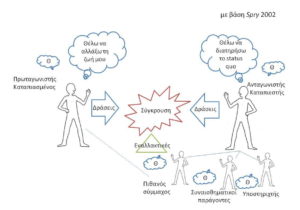

Για τον λόγο αυτό, δημιουργεί το ΘτΚ, μια διαδικασία που σκοπό έχει να μετατρέψει τον παθητικό θεατή σε ενεργό ηθοποιό, που ενδυναμώνεται και μπορεί να επέμβει στη θεατρική δράση. Για τον ίδιο, δύο είναι οι βασικές αρχές του Θεάτρου του Καταπιεσμένου: κατά πρώτον να βοηθήσει τον θεατή να γίνει πρωταγωνιστής της δραματικής πράξης και κατά δεύτερον να μεταφέρει αυτές τις δράσεις στην πραγματική ζωή (Boal 1990, 36).

Το Θεάτρου του Καταπιεσμένου: η διαδικασία

Η διαδικασία μεταμόρφωσης του παθητικού θεατή σε ενεργό ηθοποιό κατά τη διάρκεια του ΘτΚ μπορεί να πραγματοποιηθεί μέσα από τα ακόλουθα τέσσερα στάδια:

1) «Γνωριμία με το σώμα», 2)»Δημιουργία εκφραστικού σώματος», 3) «Το θέατρο ως γλώσσα» και 4) «Το θέατρο ως λόγος» (Μποάλ 1981, 21-22).

- Στο πρώτο στάδιο «Γνωριμία με το σώμα» διακρίνονται ασκήσεις που βοηθούν τους/τις συμμετέχοντες/ουσες να αντιληφθούν το σώμα τους, τα όριά του, τις δυνατότητές του, τις κοινωνικές παραμορφώσεις του καθώς και τους τρόπους που θα κατανικηθούν.

- Στο δεύτερο στάδιο «Δημιουργία Εκφραστικού Σώματος» διακρίνεται μια σειρά παιχνιδιών που βοηθούν τους/τις συμμετέχοντες/ουσες να εκφράζουν το σώμα τους χωρίς να ανατρέχουν σε πιο συνηθισμένες καθημερινές μορφές έκφρασης.

- Το τρίτο στάδιο, «το θέατρο ως γλώσσα», στοχεύει στη χρήση του θεάτρου ως μια ζωντανή και σύγχρονη γλώσσα και όχι ως ένα τελειωμένο προϊόν που αντανακλά εικόνες του παρελθόντος. Το τρίτο στάδιο ενέχει τρεις βαθμίδες: α) ταυτόχρονη δραματουργία (simultaneous dramaturgy), β) θέατρο εικόνας (image theatre) και γ) θέατρο φόρουμ (forum theatre).

- Τέλος, στο «θέατρο ως λόγος» διακρίνονται απλές μορφές θεάτρου με τις οποίες οι συμμετέχοντες/ουσες δημιουργούν θεάματα/παραστάσεις, προκειμένου να συζητήσουν συγκεκριμένα θέματα ή να δοκιμάσουν εναλλακτικές. Στο τέταρτο στάδιο ανήκουν το θέατρο-εφημερίδα (newspaper theatre), αόρατο θέατρο (invisible theatre), θέατρο φωτορoμάντζο (photo-romance theatre), απόκριση στην καταπίεση (breaking of repression), θέατρο-μύθος (myth theatre), θέατρο-κριτική (trial theatre), μάσκες και τελετές (masks and rituals) (Boal 2000, 126-156, Μποάλ 1981, 21-54).

«To θέατρο ως γλώσσα»

Θεωρώντας ότι το τρίτο στάδιο του ΘτΚ προσφέρεται ιδιαίτερα στη χρήση του θεάτρου ως εργαλείου έρευνας και κοινωνικής παρέμβασης, επιλέγεται να αναλυθεί διεξοδικά παρακάτω.

Α. Ταυτόχρονη δραματουργία

Στην πρώτη βαθμίδα γίνεται ουσιαστικά και η πρώτη πρόσκληση στο κοινό να παρέμβει στη θεατρική διαδικασία, χωρίς απαραιτήτως να συμμετέχει με τη φυσική του παρουσία επί σκηνής (Boal 2000, 132). Ουσιαστικά, κάποιος/α συμμετέχων/ουσα καταθέτει ένα θέμα/πρόβλημα που θέλει να συζητήσει. Οι ηθοποιοί είτε με αυτοσχεδιασμό είτε με σκηνοθετημένη παράσταση, παρουσιάζουν το θέμα σε μια σύντομη θεατρική ιστορία δέκα με είκοσι λεπτών. Η ιστορία παρουσιάζεται μέχρι το σημείο που εμφανίζεται το βασικό πρόβλημα, το οποίο χρειάζεται λύση. Τότε οι ηθοποιοί σταματούν την ιστορία και συζητούν με τους θεατές για τις λύσεις που οι τελευταίοι προτείνουν. Στη συνέχεια, οι ηθοποιοί δοκιμάζουν με αυτοσχεδιασμό όλες τις προτεινόμενες λύσεις που έχουν δοθεί από το κοινό. Οι θεατές έχουν τη δυνατότητα να παρέμβουν, να διορθώσουν τις δράσεις ή τα λόγια του/της ηθοποιού, ο/η οποίος/α καλείται να ακολουθήσει κατά γράμμα τις οδηγίες τους. Έτσι, ενώ το κοινό «γράφει» την ιστορία/ δραματουργία, οι ηθοποιοί ταυτόχρονα την υποδύονται (ταυτόχρονη δραματουργία). Όλες οι λύσεις, προτάσεις και απόψεις αναδεικνύονται μέσω της θεατρικής φόρμας.

Β. Το θέατρο εικόνα

Στη δεύτερη βαθμίδα, στο θέατρο εικόνα οι συμμετέχοντες/ουσες συμμετέχουν πιο ενεργά απ’ ό,τι στην πρώτη βαθμίδα, την ταυτόχρονη δραματουργία. Πιο συγκεκριμένα, ένας/μία συμμετέχων/ουσα καλείται να εκφράσει τις απόψεις του/της για ένα θέμα (αφαιρετικό ή συγκεκριμένο) χωρίς να μιλάει, αποκλειστικά χρησιμοποιώντας τα σώματα άλλων συμμετεχόντων/ουσών, οι οποίοι/ες καλούνται να παγώσουν ως αγάλματα σε μια συγκεκριμένη δράση ή στιγμή, εκφράζοντας τα συναισθήματα που θα τους δείξει ο/η συμμετέχων/ουσα-γλύπτης/τρια. Αφού ο/η γλύπτης/τρια ετοιμάσει την παγωμένη εικόνα που προτείνει, τότε μπορεί να προχωρήσει σε συζήτηση με τους/τις υπόλοιπους/ες συμμετέχοντες/ουσες για το αν συμφωνούν ή όχι με τη συγκεκριμένη άποψη στην εικόνα. Τροποποιήσεις μπορούν να συμβούν, ώστε η ιδέα που αποτυπώνεται στην παγωμένη εικόνα να είναι αποδεκτή από όλους/ες (Boal 2000, 135).

Η εικόνα αυτή, που πρέπει να είναι ακίνητη, να ενέχει μια δυναμική, καθώς αποκρυσταλλώνει όλο το νόημα της δράσης, αποτελεί την πραγματική εικόνα (real image). Οι παγωμένοι/ες συμμετέχοντες/ουσες ως αγάλματα δεν στέκουν στατικοί/ες, αλλά οφείλουν να είναι σε ετοιμότητα δράσης. Ακολούθως, σύμφωνα με τη διαδικασία του Boal, ο συμμετέχων-γλύπτης ή η συμμετέχουσα γλύπτρια καλείται να δημιουργήσει με τα σώματα των συμμετεχόντων/ουσών την ιδανική εικόνα (ideal image) της ίδιας κατάστασης, την ιδανική λύση δηλαδή στο πρόβλημα που έχει τεθεί καθώς επίσης και την εικόνα μετάβασης (transitional image) από την πρώτη εικόνα στη δεύτερη. Με άλλα λόγια, κάθε συμμετέχων/ουσα, μέσα από τις παγωμένες εικόνες μπορεί να θέσει τον προβληματισμό του/της για διάφορα θέματα που εκπροσωπούν την πραγματικότητα και πάλι μέσα από εικόνες να προτείνει την κοινωνική αλλαγή.

Γενικότερα, το θέατρο εικόνα συμβάλλει στην ανάπτυξη της κριτικής και στοχαστικής ικανότητας τόσο των συμμετεχόντων/ουσών σε αυτή όσο και των θεατών. Aπό τη μια, οι συμμετέχοντες/ουσες καλούνται να επιλέξουν το ουσιαστικό μήνυμα της εικόνας, να εστιάσουν στο νόημα, αφαιρώντας οτιδήποτε περιττό ή ασαφές και από την άλλη οι θεατές καλούνται να αναγνωρίσουν το μήνυμα της εικόνας και να εμβαθύνουν στο «πίσω κείμενο». Ο Woolland, μεταξύ άλλων, αναφέρει ότι ένα επιπλέον πλεονέκτημα του θεάτρου εικόνας είναι ότι επαναλαμβάνεται εύκολα με ακρίβεια και λεπτομέρεια (Woolland 1999, 97).

Γ. Το θέατρο φόρουμ

Τo θέατρο φόρουμ αποτελεί την τρίτη και τελευταία βαθμίδα του «θεάτρου ως γλώσσα» και εδώ το κοινό καλείται να επέμβει αποφασιστικά στη δραματική διαδικασία και να την αλλάξει. Η διαδικασία έχει ως εξής: δίνεται η ευκαιρία σε έναν/μια συμμετέχοντα/ουσα να διηγηθεί μια ιστορία με ένα πρόβλημα κοινωνικό ή πολιτικό που τον/την αφορά. Ακολούθως, παρουσιάζεται ένας σύντομος (δεκάλεπτος ή δεκαπεντάλεπτος) αυτοσχεδιασμός σχετικά με αυτό το θέμα, όπου δίνεται μία λύση στο πρόβλημα. Στο τέλος αυτής της σύντομης παράστασης, με την καθοδήγηση ενός/μιας έμπειρου/ης εμψυχωτή/τριας, του/της joker, ξεκινά μια συζήτηση με το κοινό σχετικά με το αν συμφωνούν ή όχι με τη λύση που δόθηκε. Προφανώς κάποιοι/ες θα διαφωνούν. Τότε, η παράσταση θα ξαναπαιχτεί από την αρχή, αλλά αυτή τη φορά, όσοι θεατές δεν συμφωνούν, μπορούν να έρθουν να αντικαταστήσουν τον/την ηθοποιό και να οδηγήσουν τη δράση προς την κατεύθυνση που τους φαίνεται πιο ολοκληρωμένη. Οι παρεμβάσεις των θεατών στη σκηνή καθοδηγούνται από τον/την joker, που διαμεσολαβεί ανάμεσα στη σκηνή και την πλατεία, εξηγεί τους κανόνες του θεάτρου φόρουμ στους/στις συμμετέχοντες/ουσες και τους/τις προσκαλεί να στοχαστούν και μέσα από θεατρική δράση να τοποθετηθούν στο πρόβλημα που παρουσιάζεται. Ο/η ηθοποιός που αντικαθίσταται κάθε φορά, αφήνει τη σκηνή και επιστρέφει, αφού ο/η συμμετέχων/ουσα ολοκληρώσει την επέμβασή του/της. Οι υπόλοιποι/ες ηθοποιοί οφείλουν να προσαρμοστούν στην καινούρια κατάσταση και να αντιμετωπίσουν τη νέα πρόταση που προσφέρεται από το κοινό (Μποάλ 1981, 36-37, Boal 2000, 139). Είναι σημαντικό να τονιστεί ότι στο θέατρο φόρουμ δεν επιβάλλεται καμία ιδέα. Δίνεται στο κοινό (θεατές-λαό) η δυνατότητα να δοκιμάσει όλες του τις ιδέες και λύσεις και μέσα από τις θεατρικές μεταμορφώσεις να μεταμορφωθεί πολιτικά. Ο Jonothan Neelands το ονομάζει «θέατρο των κοινωνικών και πολιτικών αλλαγών», θεωρώντας ότι η αλλαγή που διαμορφώνεται αρχικά στη φαντασία του θεατή ως πιθανότητα, αποτελεί τον σπόρο της πραγματικής αλλαγής (Neelands 2004, 22-23). Έτσι, στο θέατρο φόρουμ οι θεατές από «spectators» γίνονται «spect-actors», δηλαδή προβαίνουν σε κοινωνική δράση, κρίνουν και προβληματίζονται σχετικά με θέματα της κοινωνικής τους πραγματικότητας και τελικά ενδυναμώνονται.

Το Θέατρο του Καταπιεσμένου, που ξεκίνησε τη δεκαετία του 1960, βρήκε ιδιαίτερη απήχηση στην καταπιεσμένη από τα διδακτορικά καθεστώτα Βραζιλία και γρήγορα διαδόθηκε σε όλη τη Νότια Αμερική. Στα τέλη της δεκαετίας του 1970 οι τεχνικές του πολιτικά διωκόμενου Boal βρίσκουν μεγάλη απήχηση στην Ευρώπη, όπου καταφεύγει ως πολιτικός πρόσφυγας. Βέβαια, ενώ στη Νότια Αμερική εργαζόταν με υπαρκτές μορφές καταπίεσης όπως φτώχεια, ρατσισμό, σεξισμό, στην Ευρώπη εξετάζει μορφές καταπίεσης που δεν είναι απτές και ορατές ή που καλύτερα είναι εσωτερικές όπως ο φόβος, η μοναξιά, το άγχος. Έτσι, δημιουργεί το Ουράνιο Τόξο των επιθυμιών (The Rainbow of Desires) και το Μπάτσος στο Κεφάλι (Cops in the Head), δύο μορφές Θεάτρου του Καταπιεσμένου που αναφέρονται στην καταπίεση, η οποία έχει εσωτερικευθεί, καθώς πολλοί άνθρωποι που καταπιέζονται, δεν αντιδρούν και παύουν να αγωνίζονται. Αργότερα, δημιουργεί το Νομοθετικό Θέατρο (Legislative Theatre) με το οποίο οι ίδιοι οι πολίτες, μέσα από τη θεατρική διαδικασία, καταλήγουν σε προτάσεις προς τη Βουλή για αποφάσεις, διατάγματα, νόμους που αφορούν την κοινωνία τους. Σήμερα, οι μορφές και τεχνικές του ΘτΚ είναι πολύ διαδεδομένες σε πολλές χώρες και χρησιμοποιούνται από εκπαιδευτικούς, θεατρικές ομάδες, ακτιβιστές με ποικίλους τρόπους: ως μορφή άμεσης κοινωνικής δράσης με σκοπό την καταγγελία καταπιεστικών δομών και σχέσεων, ως μέθοδοι κοινωνιολογικής έρευνας, ως μέσο για την ενδυνάμωση ευαίσθητων κοινωνικά ομάδων, ως διδακτικό μέσο για την προσέγγιση διαφορετικών γνωστικών αντικειμένων, ως μορφή ψυχαγωγίας (Κατσαρίδου 2014, 79).

ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓΡΑΦΙΑ

Βασιλειάδη, Kορίνα (2012) Το Θέατρο της Κοινότητας, το Θέατρο για την Ανάπτυξη και το Εφαρµοσµένο Δράµα µέσα από τα παραδείγµατα του Teatro Povero (Ιταλία), της Adugna Community Dance Theatre (Αιθιοπία) και της εφαρµογής στο Etnisk Radgivningcenter Noor (Δανία) διπλωµατική διπλωματική εργασία, Τμήμα Θεάτρου Αριστοτέλειο Πανεπιστήμιο Θεσσαλονίκης (διαθέσιμο στο http://ikee.lib.auth.gr/record/129777/files/GRI-2012-9154.pdf)

Billingham, Peter (επιμ.), (2005) Radical Initiatives in Inteventionist & Community Drama, Bristol & Portland: Intellect Books.

Boal, Augusto, (1990) «The cops in the Head, Three Hypotheses» στο The Drama Review, τχ. 34, τμ. 3, Φθινόπωρο 1990.

Boal, Augusto, (1995) The rainbow of desire: The Boal method of theatre and therapy, London & New York: Routledge.

Boal, Augusto, (1998) Legislative theatre, London & New York: Routledge.

Boal, Augusto, (2000) Theatre of the Oppressed. London: Pluto Press.

Boal, Augusto, (2006) The Aesthetics of the Oppressed, London: Routledge.

Boal, Augusto, (2009) Message of World Theatre Day 2009. [Online] Paris: International Theatre Institute (ITI). (διαθέσιμο στο http://www.world–theatre– day.org/en/picts/WTD_Boal_2009)

Boal, Augusto, (2013) Θεατρικά παιχνίδια για ηθοποιούς και για μη ηθοποιούς, , Θεσσαλονίκη: Σοφία.

Κατσαρίδου Μάρθα, (2014) Η Θεατροπαιδαγωγική μέθοδος, Μια πρόταση για τη διδασκαλία της λογοτεχνίας σε διαπολιτισμική τάξη, Θεσσαλονίκη: Σταμούλη.

Katsaridou, Martha, και Vío, Koldobika, «Theatre of the Oppressed as a tool of educational and social intervention the case of Forum Theatre», στο Grollios, George, Liambas, Anastassios, και Pavlidis, Perikles (επιμ.), 4th International Conference on Critical Education “Critical Education in the Era of Crisis”, 2015 (διαθέσιμο στο https://www.academia.edu/36657233/Theatre_of_the_Oppressed_as_a_tool_of_educational_and_social_intervention_the_case_of_Forum_Theatre

Μποάλ, Αουγκούστο, (1981) Το θέατρο του καταπιεσμένου, μτφρ. Μπραουδάκη, Ελπίδα, Αθήνα: Θεωρία.

Neelands, Jonothan, (2004) «Θέατρο και Μεταμορφώσεις: Πώς το θέατρο μας βοηθάει να δούμε ποιοι είμαστε και πως αλλάζουμε», στο Γκόβας, Νίκος (επιμ.), Το θέατρο και οι παραστατικές τέχνες στην εκπαίδευση, Δημιουργικότητα και Μεταμορφώσεις, Πρακτικά της 4ης Διεθνούς Συνδιάσκεψης για το Θέατρο στην Εκπαίδευση, Αθήνα: Δίκτυο για το Θέατρο στην Εκπαίδευση. σ. 22-23.

Nicholson Helen (2014) Applied drama, The gift of theatre, Hampshire & N. York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Prendergast, Monica, και Saxton, Juliana (επιμ.), (2009) Applied Theatre Bristol & Chicago: Intellect.

Somers, John, «“Θέατρο της Κοινότητας” στο αγροτικό Devon: ένα εναλλακτικό μοντέλο», Εκπαίδευση & Θέατρο 3, 2003 (διαθέσιμα στο http://theatroedu.gr/DesktopModules/EasyDNNNews/DocumentDownload.ashx?portalid=0&moduleid=428&articleid=2017&documentid=243)

Spry, Lib, (2006) «Structures of Power. Toward a theatre of liberation», στο Cohen-Cruz, Jan, και Schutzman, Mady, (επιμ.), A Boal Companion, Dialogues on theatre and cultural politics. New York & London: Routledge.

Thompson, James, και Schechner, Richard, «Why “Social Theatre”?», TDR, Τόµος 48, Τεύχος 3, 2004.

Woolland, Brian, (1999) Η διδασκαλία του Δράματος στο δημοτικό σχολείο, Ρόλοι στη ζωή & ρόλοι στο θέατρο, μτφρ. Κανηρά, Ελένη, Αθήνα: Ελληνικά Γράμματα.

[1]* Επίκουρη καθηγήτρια, Παιδαγωγικό Τμήμα Προσχολικής Εκπαίδευσης, Πανεπιστήμιο Θεσσαλίας

[2] ** Θεατροπαιδαγωγός, Σκηνοθέτης

SOCIAL THEATRE: COMMUNITY THEATRE & THEATRE OF THE OPPRESSED

Martha Katsaridou [1]*

Koldo Vío [2]**

The Social Theatre

Social Theatre is one of the key areas of Applied Theatre that aims at social action/intervention, participation, empowerment and ultimately social transformation. “Art is not merely contemplation, it is also action, and all action changes the world, at least a little” (Tony Kushner in Nicholson 2014, 10).

The term Social Theatre is widely used by countries such as Italy, Spain, Portugal and recently Greece, while in the Anglo-Saxon world, respectively, the terms community-based theatre, popular theatre, theatre for development, theatre for social intervention are more commonly used. Special mention, however, needs to be made of Richard Schechner and James Thompson (2004), who come from the field of performance studies and adopt the term Social Theatre, seeking a unifying line on the forms it can take. Specifically, Social theatre may be “defined as theatre with specific social agendas;theatre where aesthetics is not the ruling objective; theatre outside the realm of commerce, which drives Broadway/the West End, and the cult of the new, which dominates the avantgarde” (Thompson & Schechner 2004, 12).

For them, Social Theatre can take place in a variety of places with different participant(s). Examples of places include prisons, refugee reception areas, hospitals, schools, orphanages, and nursing homes. Similarly, participants in social theatre activities may be local residents, people with disabilities, refugees, prisoners and, more generally, people belonging to vulnerable, disadvantaged and marginalized groups. They may also be people who have lost touch with a sense of groupness, people who are internally and externally marginalized and homeless.

In general, Social Theatre is performed in places and under conditions that are not typically understood as ‘theatre’. Social Theatre animators are usually professionals –often artists, but this is not necessary– and act more as ‘facilitators’, helping the group to participate actively by involving themselves in the process. The participants, on the other hand, are non-theatre professionals, ‘non-actors’, who during the action become actors (Thompson & Schechner 2004, 12; Vassiliadis 2012, 17).

Next, two very important forms of Social Theatre are selected and analyzed, forms that are linked to social action and change.

Community Theatre

Community Theatre has its roots in a very specific context in which the content, the participants and the themes are local. The diversity that distinguishes the forms and performances of Community Theatre has also led to the need to use different terms to describe each situation. Prendergast and Saxton cite the following terms as examples: “grassroots theatre,” “local theatre,” “ensemble theatre,” “people’s theatre.” As they underline “whatever the name, the emphasis is on creating and performing the stories of communities and community members in original productions that are specifically local. These stories may be celebratory or critical, or a combination of both” (Prendergast and Saxton 2009, 135). They also distinguish between the terms “community based theatre” and “community theatre”, arguing that the first as a form of Applied Theatre refers to professional theatre while the latter refers to amateur theatre performances where older scripts are presented to random audiences.

In his study John Bull notes the various forms of Community Theatre that we encounter in order to consider the important issues that arise when attempting to categorize Community Theatre (Bull in Billingham 2005, 9).

In particular, he distinguishes the following forms: (a) amateur community theatre groups; (b) youth theatre groups; (c) community theatre in the professional theatre; (d) theatre-in-education; (e) educational community group,) f) special interest theatre companies; g) theatre in the workplace; h) one-off community celebrations, festivals; i) theatre from within the community; j) theatre for the community (Bull in Billingham 2005, 9-11).

From the above it can be seen that the term ‘community theatre’ is used in a variety of ways to describe forms of theatre that vary greatly from one another depending on the objective, the motivation for participation, the context in which the performance is presented, the venue chosen and the audience targeted, the funding received, etc.

Bull argues that fundamentally this issue arises because, as is usually the case with other social and cultural terms, the concept of community is not neutral. Originating from the Latin root communitatem, “its usage has been associated with a sharing of common interests, and also a sharing of common location” (Bull in Billingham 2005, 11). The notion of community can be seen as more than a group of people who happen to live in one particular area rather than another; instead, it is a more substantial connection, probably initiated by the common geographical location of individuals who share a sense of a common and group ideology (whether political or class), which may be determined according to issues such as sexuality, gender, origin, religious beliefs or whatever (Bull in Billingham 2005, 11).

According to the above categories, it is of particular interest that depending on the form of the Community Theatre, the participation of the community members may vary, but the social action and intervention for the community itself remains constant. For example, in the category ‘Theatre through the Community’, the whole process –from the actors involved, to the theatrical text either written by a member of the community or collectively created, to the funding provided– is entirely based on the community itself. The aim is to give the rest of the community narratives and personal stories that are relevant to everyone. The venue for the theatre activity can be a local theatre or even any non-theatre venue.

For Bull, closely related to the above form is “Theatre for the Community” with the significant difference that this category involves professional theatre groups, working for a period of time in and for a particular community. Clearly, as the performance put on by the professional(s) in the field, addresses specific community issues, close and honest collaboration between the company and the community members themselves is necessarily required. The themes of the performances are chosen after relevant research by the collaborating artists with the community and are presented theatrically by professional artists in front of the community. The aim of the performances is to tell the life of the community and its history. Thus, in the performance, community members are confronted with themselves, the perspective they adopt about things and the perspective the performance puts on local events. They reflect, they connect individual interest with collective consciousness and, depending on the degree of audience participation in the theatrical action, the experience can range from recreational to therapeutic (Bull in Billingham 2005, 10-11; Vassiliadou 2012, 12-13).

At this point and in order to analyze the collaboration of animators and external collaborators with a community to discuss its issues through theatrical language, Bull proposes the term ‘interventionist community theatre’, i.e. “a theatre that seeks to directly affect the lives of its targeted audiences” (Bull in Billingham 2005, 13). The notion of community, linked to the particularities of the area in question, is central to many projects and very often works to offer an alternative vision of how things have been or how they might be in the future.

The Theatre of the Oppressed: basic principles

Augusto Boal, Brazilian theatre director, theatre educator, writer, playwright and politician is the creator of the Theatre of the Oppressed, hereafter referred to as TO.

As a theoretical framework and an aesthetic approach, TO is based on theatrical game exercises and dramatic techniques, which make up an interactive and participatory kind of theatre aimed at social change.

“We are all actors: being a citizen is not living in society, it is changing it”, Boal says in his message for World Theatre Day 2009 (Boal 2009).

Setting as its goal the critical awareness of reality and the search for alternatives to social, interpersonal and personal problems, TO is based on Paulo Freire’s work, Pedagogy of the Oppressed. This book later became a milestone for the Critical Pedagogy movement, i.e., the current of theoretical pedagogical thought and educational practice that emerged in the early 1980s in the United States.

For Augusto Boal, the theatre and more specifically the “Poetics of the Oppressed” is first and foremost a poetics of liberation. The spectator delegates no right for others to act or think in his place. He is liberated, acts and thinks for himself. Theatre is action (Boal 1981, 54; Katsaridou 2014, 78). In particular, Boal states that “theatre should be a rehearsal for action in real life, rather than an end in itself” (Boal 2006, 6). Boal treats theatre as a ‘language’, a language that can be used by anyone, whether or not they are inclined to the artistic field. He wants “to show in practice how the theatre can be placed at the service of the oppressed, so that they can express themselves and so that, by using this new language, they can also discover new concepts” (Boal 2000, 121).

For this reason, he creates the TO, a process that aims to transform the passive spectator into an active actor, empowered and able to intervene in theatrical action. For him, two are the basic principles of the Theatre of the Oppressed: first, to help the spectator become a protagonist of the dramatic action and second, to apply these actions to real life (Boal 1990, 36).

The Theatre of the Oppressed: the process

The process of transforming the passive spectator into an active actor during the TO can be carried out through the following four stages:

1) “Knowing the body”, 2) “Making the body expressive”, 3) “The Theatre as language” and 4) “Theatre as discourse” (Boal 2000, 126).

- The first stage “Knowing the body” consists of exercises that help the participants to understand their body, its limits, its possibilities, its social deformations and the ways in which they will be overcome.

- In the second stage “Making the body expressive”, a series of games is distinguished that help participants to express their bodies without resorting to more common everyday forms of expression.

- The third stage, “The Theatre as discourse”, aims to use theatre as a living and contemporary language rather than as a finished product reflecting images of the past. The third stage involves three stages: a) simultaneous dramaturgy, b) image theatre and c) forum theatre.

- Finally, “Theatre as a discourse” distinguishes simple forms of theatre in which participants create spectacles/performances in order to discuss specific issues or to try out alternatives. The fourth stage includes newspaper theatre, invisible theatre, photo-romance theatre, breaking of repression, myth theatre, trial theatre, masks and rituals (Boal 2000, 126-156; Boal 1981, 21-54).

“The Theatre as a language”

Considering that the third stage of TO is particularly suited to the use of theatre as a tool for research and social intervention, it is chosen to be analyzed in detail below.

Α. Simultaneous dramaturgy

The first degree is essentially the first invitation to the audience to intervene in the theatrical process, without necessarily participating with their physical presence on stage (Boal 2000, 132). Essentially, a participant submits an issue/problem that he/she wants to discuss. The actors, either through improvisation or staged performance, present the topic in a short ten to twenty minute theatre story. The story is presented up to the point where the main problem appears, which needs a solution. Then the actors stop the story and discuss with the audience the solutions that the latter propose. Then the actors improvisationally try out all the suggested solutions given by the audience. The spectators have the possibility to intervene, to correct the actions or the words of the actor, who is asked to follow their instructions to the letter. Thus, while the audience “writes” the story/dramaturgy, the actors simultaneously act it out (simultaneous dramaturgy) (Boal 2000, 134). All solutions, suggestions and opinions are brought out through the theatrical form.

Β. Image theatre

On the second degree, in the image theatre participants are more actively involved than in the first level, simultaneous dramaturgy. More specifically, a participant is invited to express his/her views on a topic (abstract or concrete) without speaking, exclusively using the bodies of other participants, who are invited to freeze as statues in a particular action or moment, expressing the emotions shown by the participant-sculptor. After the sculptor/s have/s prepared the frozen image he/she proposes, then he/she can proceed to a discussion with the other participants on whether or not they agree with the particular viewpoint in the image. Modifications can occur so that the idea captured in the frozen image is acceptable to all (Boal 2000, 135).

This image, which must be still, involves a dynamic as it crystallizes the whole meaning of the action, it constitutes the real image, the actual image. The frozen participants as statues do not stand static, but have to be in readiness for action. Subsequently, according to Boal’s procedure, the sculptor-participant is asked to create with the bodies of the participants the ideal image of the same situation, i.e. the ideal solution to the problem that has been posed as well as the transitional image from the first image to the second. In other words, each participant, through the frozen images, can raise his/her concerns about various issues representing the reality and again through images to propose the social change.

More generally, image theatre contributes to the development of the critical and reflective capacity of both participants and spectators. On the one hand, participants are asked to select the essential message of the image, to focus on the meaning, removing anything unnecessary or unclear, and on the other hand, spectators are asked to recognize the message of the image and to delve into the “back text”. Woolland, among others, states that an additional advantage of image theatre is that it is easily repeated with precision and detail (Woolland 1999, 97).

- Forum Theatre

Forum theatre is the third and last degree of “theatre as language” and here the participant has to intervene decisively in the dramatic action and change it. The process is as follows: a participant is given the opportunity to tell a story about a social or political problem that concerns him/her. Subsequently, a short (ten or fifteen minute) improvisation on this topic is presented, in which a solution to the problem is given. At the end of this skit, under the guidance of an experienced animator, the joker, a discussion with the audience is initiated on whether or not they agree with the solution given. Obviously some will disagree. Then, the scene will be played again from the beginning, but this time, any participant in the audience who doesn’t agree can come in to replace any actor and lead the action in the direction that seems more appropriate to him/her. The spectators’ interventions on stage are guided by the joker, who mediates between the stage and the audience, explains the rules of the forum theatre to the participants, invites them to reflect and through theatrical action to position themselves on the problem presented. The actor, who is replaced each time, leaves the stage and returns after the participant has completed his/her intervention. The other actor(s) has/-ve to adapt to the new situation and face the new proposal offered by the audience (Boal 1981, 36-37; Boal 2000, 139). It is important to stress that no idea is imposed in forum theatre. The audience (audience-people) is given the opportunity to try out all their ideas and solutions and through theatrical transformations to be politically transformed. Jonothan Neelands calls it “theatre of social and political change”, considering that the change initially formed in the spectator’s imagination as a possibility, is the seed of real change (Neelands 2004, 22-23). Thus, in forum theatre, spectators move from being ‘spectators’ to ‘spect-actors’, i.e. they engage in social action, judging and reflecting on issues of their social reality and ultimately become empowered.

The Theatre of the Oppressed, which began in the 1960s, found particular resonance in the oppressed doctoral regimes of Brazil and quickly spread throughout South America. In the late 1970s, the techniques of the politically persecuted Boal found great resonance in Europe, where he took refuge as a political refugee. Of course, while in South America he was working with existing forms of oppression such as poverty, racism and sexism, in Europe he was examining forms of oppression that are not tangible and visible or that are better described as internal such as fear, loneliness and anxiety. Thus, he creates the Rainbow of Desires and Cops in the Head, two forms of the Theatre of the Oppressed that address oppression that has become internalized, as many people who are oppressed do not react and cease to struggle. Later, he creates Legislative Theatre in which citizens themselves, through the theatrical process, come up with proposals to Parliament for decisions, decrees, laws that affect their society. Today, the forms and techniques of the TO are very widespread in many countries and are used by teachers, theatre groups, activists in various ways: as a form of direct social action to denounce oppressive structures and relations, as methods of sociological research, as a means of empowering socially sensitive groups, as a teaching tool to approach different subjects and as a form of entertainment (Katsaridou 2014, 79).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Billingham, Peter (ed.), (2005) Radical Initiatives in Inteventionist & Community Drama, Bristol & Portland: Intellect Books.

Boal, Augusto, (1981) Το θέατρο του καταπιεσμένου, [The Theatre of the Oppressed], translation Braoudaki, Elpida, Athens: Theoria.

Boal, Augusto, (1990) ‘The cops in the Head, Three Hypotheses’ in The Drama Review, Vol. 34, Vol. 3, Autumn 1990.

Boal, Augusto, (1995) The rainbow of desire: The Boal method of theatre and therapy, London & New York: Routledge.

Boal, Augusto, (1998) Legislative theatre, London & New York: Routledge.

Boal, Augusto, (2000) Theatre of the Oppressed, London: Pluto Press.

Boal, Augusto, (2006) The Aesthetics of the Oppressed, London: Routledge.

Boal, Augusto, (2009) Message of World Theatre Day 2009. [Online] Paris: International Theatre Institute (ITI) (available at http://www.world-theatre- day.org/en/picts/WTD_Boal_2009)

Boal, Augusto, (2013) Θεατρικά παιχνίδια για ηθοποιούς και για μη ηθοποιούς, , [Theatre games for actors and non-actors], Thessaloniki: Sophia.

Katsaridou Martha, (2014) Η Θεατροπαιδαγωγική μέθοδος, Μια πρόταση για τη διδασκαλία της λογοτεχνίας σε διαπολιτισμική τάξη [The Theatropedagogical Method, A proposal for the teaching of literature in an intercultural classroom], Thessaloniki: Stamatouli.

Katsaridou, Martha, and Vío, Koldobika, “Theatre of the Oppressed as a tool of educational and social intervention the case of Forum Theatre”, in Grollios, George, Liambas, Anastassios, and Pavlidis, Perikles (eds.), 4th International Conference on Critical Education “Critical Education in the Era of Crisis“, 2015 (available at https://www.academia.edu/36657233/Theatre_of_the_Oppressed_as_a_tool_of_educational_and_social_intervention_the_case_of_Forum_Theatre

Neelands, Jonothan, (2004) “Θέατρο και Μεταμορφώσεις: Πώς το θέατρο μας βοηθάει να δούμε ποιοι είμαστε και πως αλλάζουμε” [Drama and Transformation: how drama can help us see who we are and who we are becoming], in Govas, Nikos (ed.), Το θέατρο και οι παραστατικές τέχνες στην εκπαίδευση, Δημιουργικότητα και Μεταμορφώσεις [Theatre and the Performing Arts in Education, Creativity and Metamorphosis], Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Theatre in Education, Athens: Hellenic Theatre/Drama & Education Network. pp. 22-23.

Nicholson Helen (2014) Applied drama, The gift of theatre, Hampshire & N. York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Prendergast, Monica, and Saxton, Juliana (eds.), (2009) Applied Theatre Bristol & Chicago: Intellect.

Somers, John, “«Θέατρο της Κοινότητας» στο αγροτικό Devon: ένα εναλλακτικό μοντέλο” [Community Theatre” in rural Devon: an alternative model], Education & Theatre 3, 2003 (available at http://theatroedu.gr/DesktopModules/EasyDNNNews/DocumentDownload.ashx?portalid=0&moduleid=428&articleid=2017&documentid=243)

Spry, Lib, (2006) ‘Structures of Power. Toward a theatre of liberation’, in Cohen-Cruz, Jan, and Schutzman, Mady, (eds.), A Boal Companion, Dialogues on theatre and cultural politics. New York & London: Routledge.

Thompson, James, and Schechner, Richard, “Why “Social Theatre”?”, TDR, Volume 48, Issue 3, 2004.

Vassiliadi, Korina (2012) Το Θέατρο της Κοινότητας, το Θέατρο για την Ανάπτυξη και το Εφαρµοσµένο Δράµα µέσα από τα παραδείγµατα του Teatro Povero (Ιταλία), της Adugna Community Dance Theatre (Αιθιοπία) και της εφαρµογής στο Etnisk Radgivningcenter Noor (Δανία) [Community Theatre, Theatre for Development and Applied Drama through the examples of Teatro Povero (Italy), Adugna Community Dance Theatre (Ethiopia) and the application at Etnisk Radgivningcenter Noor (Denmark)], master dissertation, Department of Theatre, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (available at http://ikee.lib.auth.gr/record/129777/files/GRI-2012-9154.pdf)

Woolland, Brian, (1999) Η διδασκαλία του Δράματος στο δημοτικό σχολείο, Ρόλοι στη ζωή & ρόλοι στο θέατρο [The Teaching of Drama in the Primary School, Roles in Life & Roles in Theatre], translation Kanira, Eleni, Athens: Ellinik

[1]* Assistant Professor, Department of Early Childhood Education, University of Thessaly, Greece

[2] ** Theatre educator, Director